Art Library – Collection of Photography

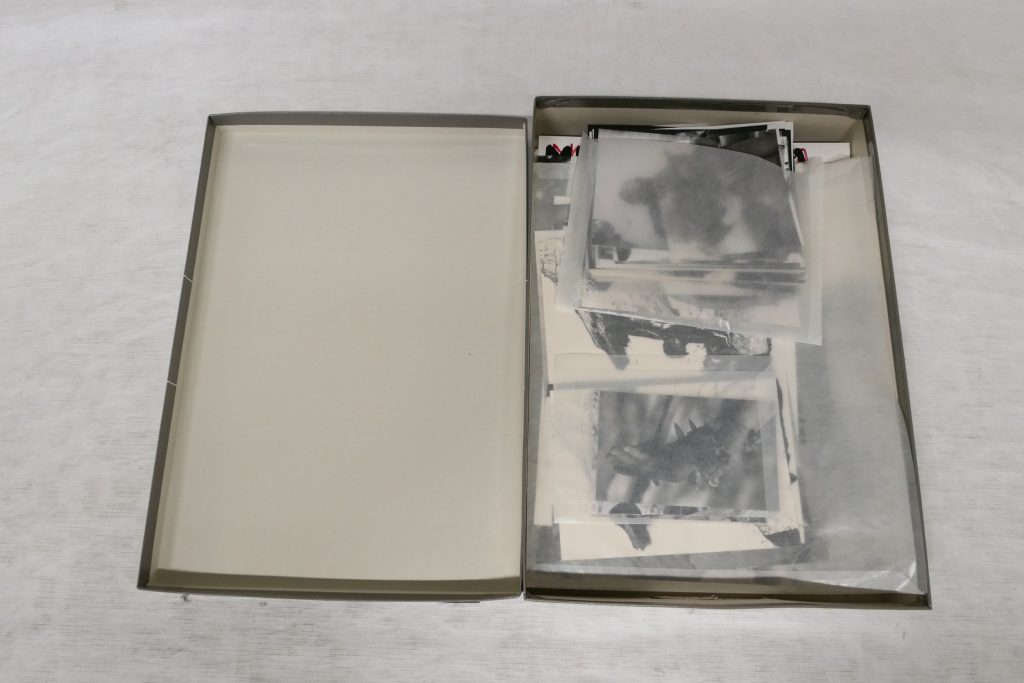

Storage in the Museum for Photography (photo: August Haverkamp)

Storage in the Museum for Photography (photo: August Haverkamp)

The photographs in the Riefenstahl estate

The stock of photographic material in the estate, comprising some 100,000 items, is held in the storage facilities of the Sammlung Fotografie der Kunstbibliothek (Art Library – Collection of Photography) at the Museum für Fotografie (Museum of Photography) in Berlin. One consideration in housing the material was ensuring that it would still be possible to reconstruct the original storage conditions at Riefenstahl’s house in Pöcking (fig 1). She had kept the photographs in several parts of the building. Specially made boxes covered with linen were kept in the living room; these contained prints in a variety of formats, sorted according to the various film and photo projects she was involved in or thematically, e.g. “L.R. portrait”, “L.R. in the mountains” and “Friends and acquaintances”. In the spacious archive room in the basement, repro negatives, negatives and prints intended for reproduction were deposited in an extensive system of drawers.

The holdings were compiled and augmented over a period of many decades. Riefenstahl seems to have primarily treated the photographic archive as a work archive: from the 1980s onwards it increasingly formed the basis for publications, for producing new prints to be shown in exhibitions, or for commercial use. The items in the collection can be roughly divided into several different groups:

(photo: © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Kunstbibliothek / Wilfried Petzi)

Albums

There are some 40 photo albums containing images from Riefenstahl’s childhood and teenage years, shots of her family, individual trips, and the birthday parties she celebrated later in life, as well as compilations about various films, and documentation of her houses under construction in Berlin and Pöcking.

Vintage and later prints

Riefenstahl had already been the subject of portraits taken by prominent photographic studios (mostly based in Berlin) when she was working as a dancer and actress. There are stills from most of the films in which she acted; cinemas often displayed these in showcases for advertising purposes. Das Blaue Licht (The Blue Light, 1932), the first film that Riefenstahl ever directed, was accompanied by numerous stills and production photos. Many more prints of this kind were added over time, especially for her Olympia documentary and the projects she worked on after the war. Riefenstahl often employed several stills photographers to accompany the shoot on-set. Her own career as a photographer began when she travelled to Africa. Prints of the images she regarded as particularly successful exist in multiple variants.

Negatives

In her work as a photographer, Riefenstahl primarily used 35mm film, although she sometimes also had recourse to medium-format cameras. In addition to her own negatives, those produced by the on-set stills photographers have also been preserved. There is a wide range of negative material with a particular focus on pictures of the Olympia film and book.

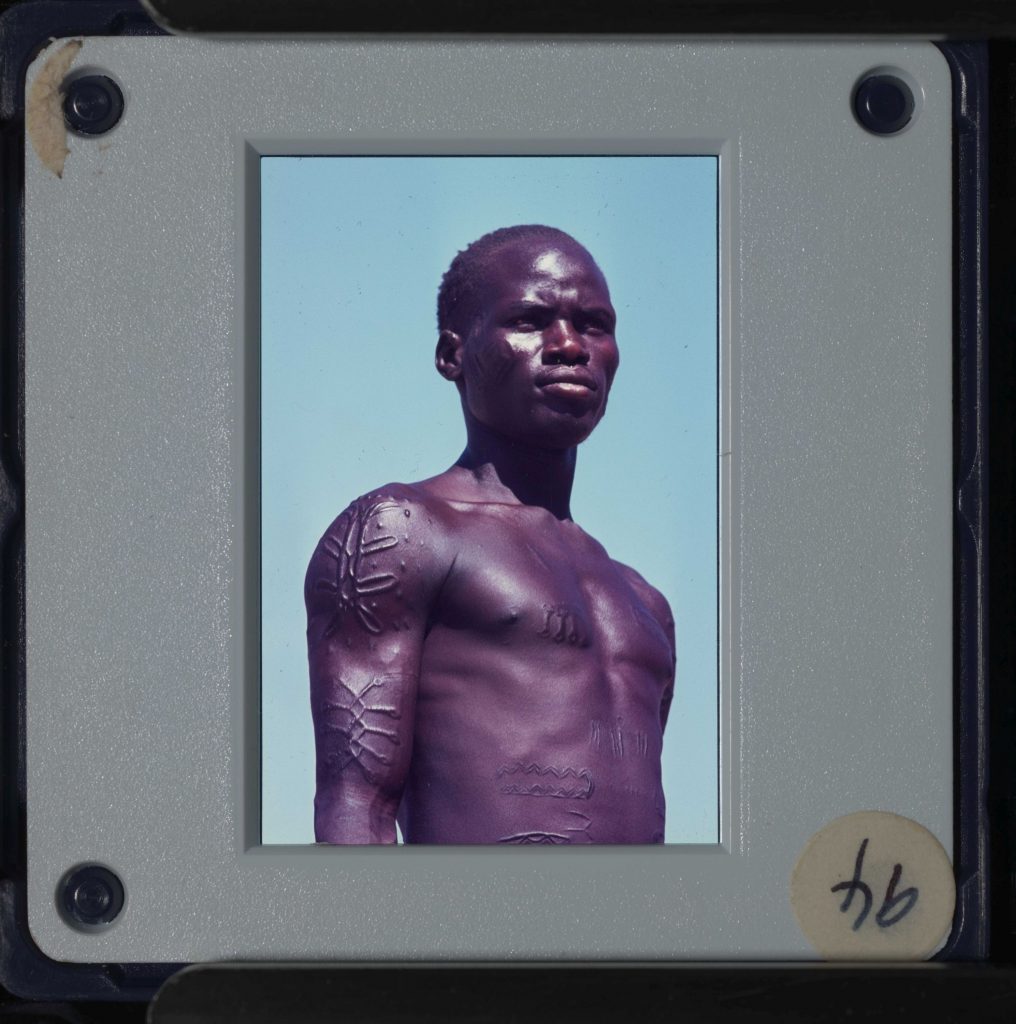

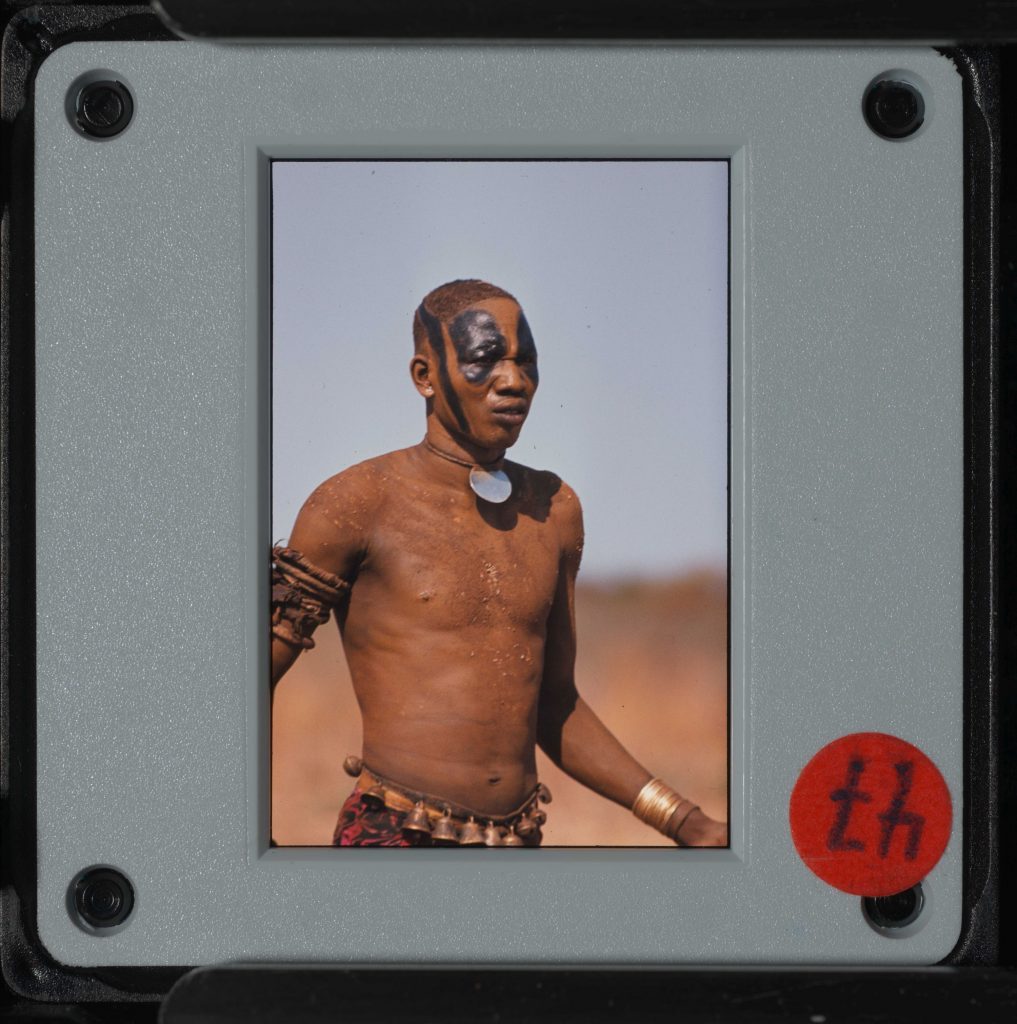

Color transparencies

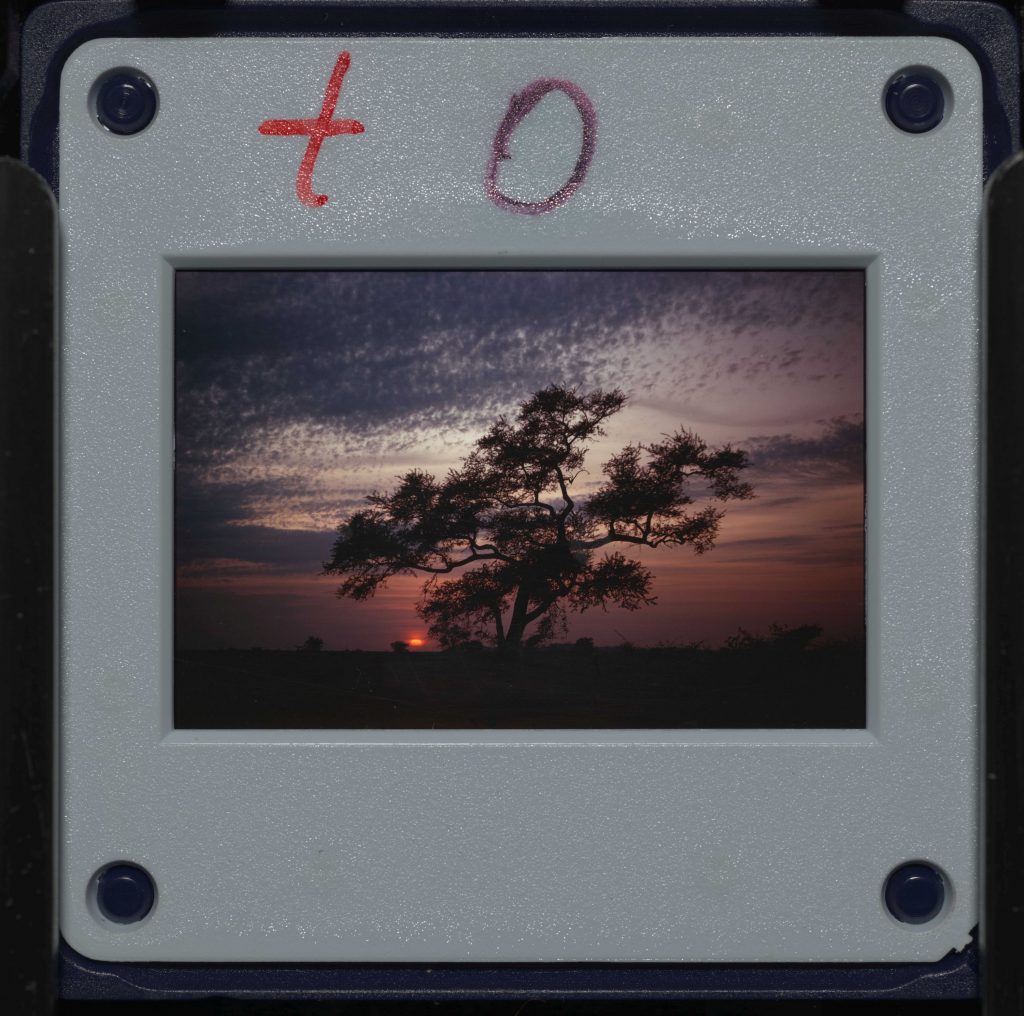

From the mid-1960s onwards, Riefenstahl used often 35mm color transparency film, particularly for the photographs she took in Africa, the journalistic features commissioned late in her career and her underwater photographs. Since the slides could be duplicated quickly and inexpensively, many of these images in the archive have a large number of duplicates, which vary considerably in their state of preservation.

LD

Working with the photographic archive

The photographic estate is a working archive which Leni Riefenstahl was still actively using until shortly before her death; it was subsequently managed by Horst Kettner, Riefenstahl’s husband and sole heir. The materials are categorised and stored according to their function, e.g. book publications. The archive is generally organised into categories that correspond to topics and narratives established by Riefenstahl herself. Nevertheless, the manner in which the materials have been stored is inconsistent. Although they were indeed sorted by topic, these contexts were often suspended and the photographs filed in other places. For example, individual slides that had been framed when initially developed were removed from their boxes and added to others.

This makes it difficult to reconstruct individual films and the contexts of their production. Very little factual information is included on the slides or prints, such as the date or location where they were created. The materials themselves range considerably: negatives in a variety of formats, slides, prints on paper (colour as well as black and white) in a wide variety of sizes and qualities (both vintage and more recent). A number of copies and derivatives such as slide duplicates, internegatives and “master duplicates” of widely varying quality can also be found in the collection. Determining any sort of qualitative hierarchy among the photographs is simply not possible.

The first step in working with the archive was to consecutively number all of the packed units (referred to here as “sets”of objects) just as they had been retrieved from Riefenstahl’s home in Pöcking room by room before the estate was transferred to Berlin. This system of numbering enabled us to create the first tabular overview of the entire estate in late 2018. In 2022, the sets relating to Africa/Nuba were separated out for further assessment and processing (fig. 1).

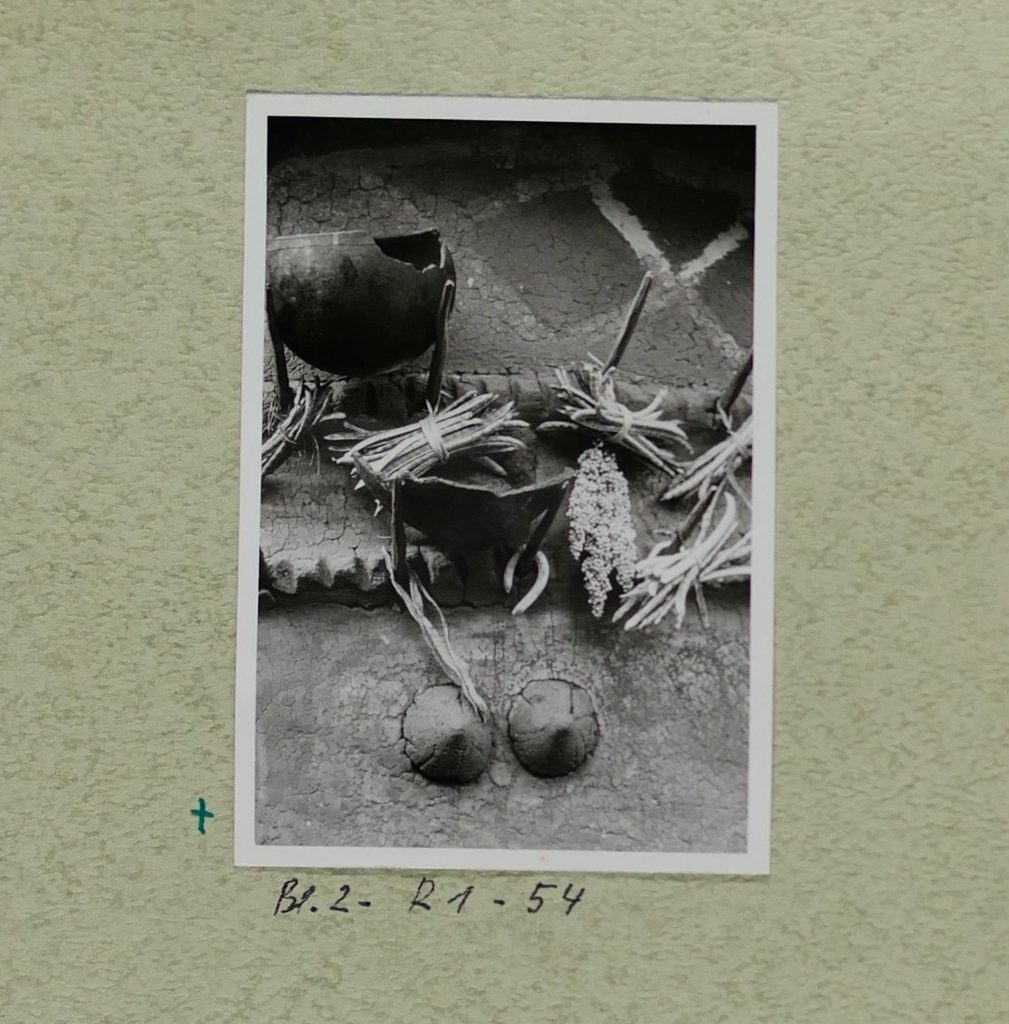

The Africa holdings contain around 45,000 photographic objects and additional archival materials, comprising just under half of the entire estate. The photographic materials were kept in a variety of containers including photo storage boxes, portfolios, document folders and cartons (figs 2&3). Archival materials such as notes and letters were discovered in the various containers and photo albums.

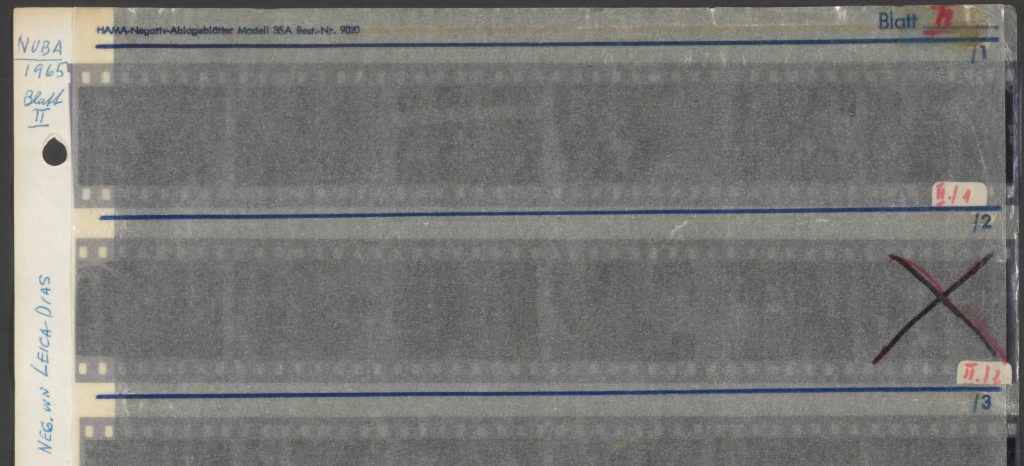

For the Nuba project, around 30,000 35mm slides were digitised in 2022/23. This underlying process formed the basis for cooperating with the project partners about the contents. It also provided insights into the way Riefenstahl worked. Later, the photo prints were also digitised and then matched up with the slides. An entry for each set of objects was made in the internal database with the aim of providing a thematic overview of the Africa holdings (fig. 4). The amounts, types, techniques and dimensions of the materials were recorded as accurately as possible. References were also made to the contents of other sets (numbering, etc.) and topics (expeditions, travels, etc.), references to the objects’ condition as well as contextual keywords and any people who were involved.

JH

Bringing light to the darkness – cataloguing the photographic archive

Artistic estates received by museums and archives are often already structured and indexed, which can be of great help to researchers. Although Leni Riefenstahl’s archive is organised according to specific principles, a structured index is lacking. Whereas many photographers organise their work chronologically, thematically and according to technical criteria, today we can only guess at what Riefenstahl’s system might have been. Riefenstahl and her staff modified the archive’s structure all too often: the photographic material was repeatedly recontextualised, parts of it were merged with other material and an incalculable number of duplicates was made. Some of the materials include descriptions that are illegible or absent. Where containers have been reused, their old labelling can be misleading.[1] Nevertheless, written documents and archival materials can help us decipher these references. The following examples are intended to aid users searching for connections within the archive.

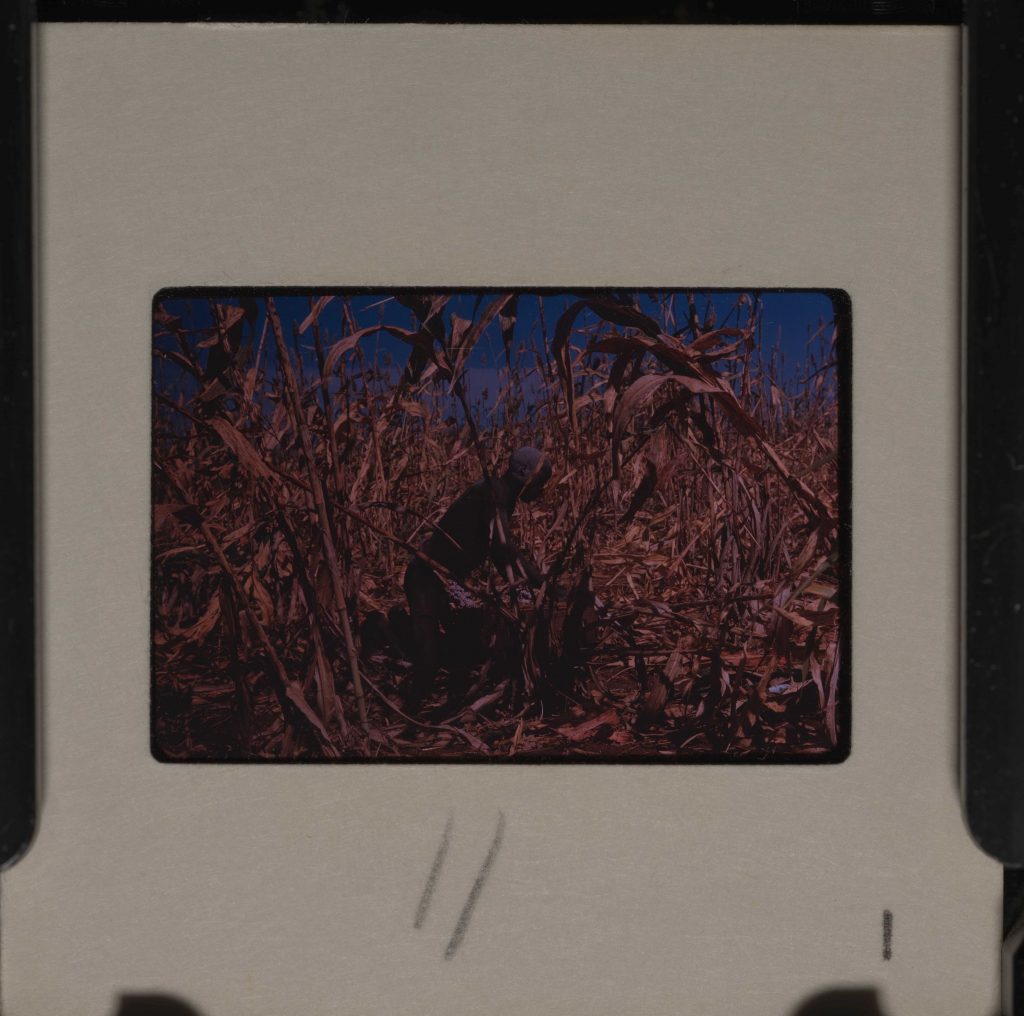

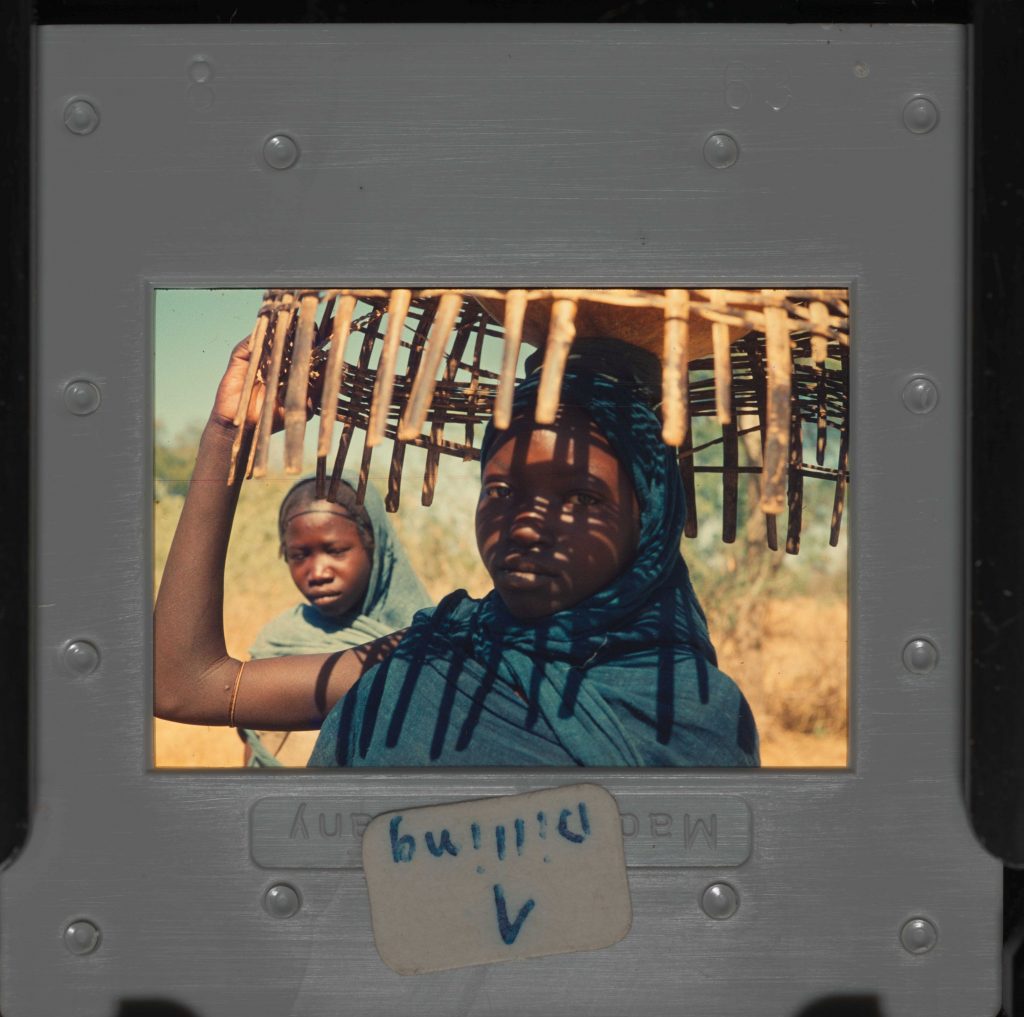

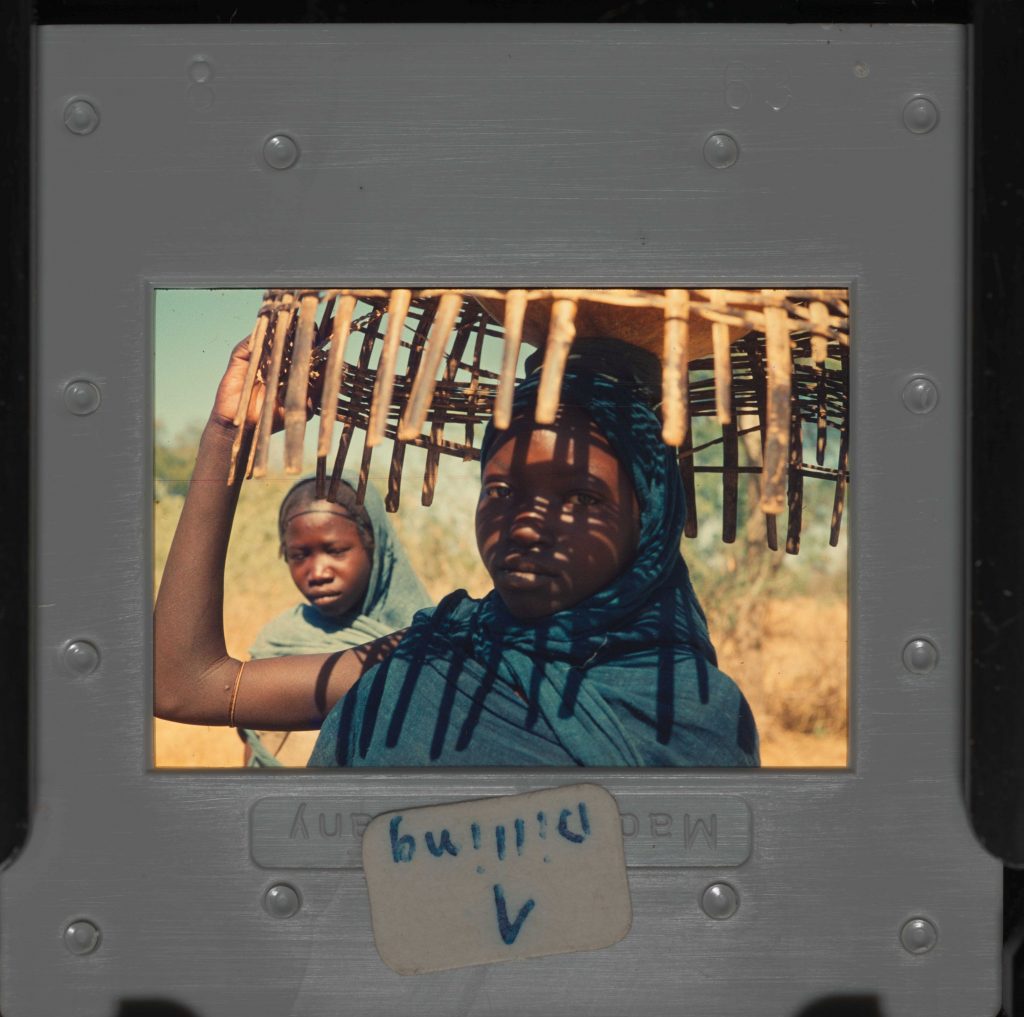

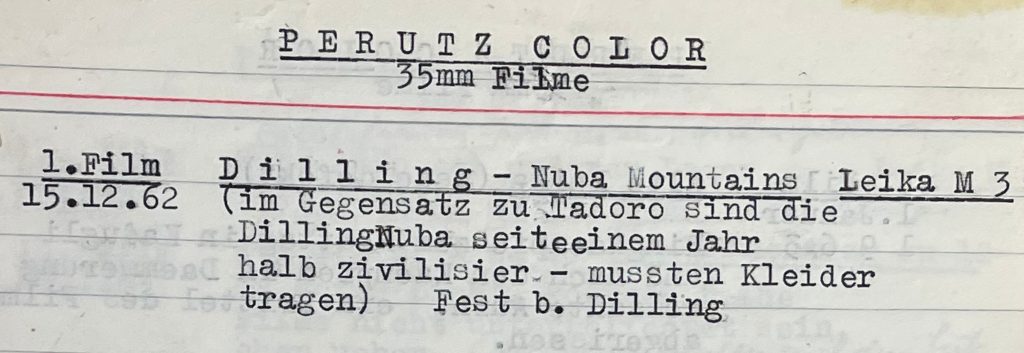

Travel documentaries

During her travels with the Deutsche Nansen-Gesellschaft (German Nansen Society) in 1962/63, Riefenstahl kept a notebook for her photographic work titled “Reports and records […] of all photographs”[2], which contained detailed lists of film rolls. Many of the framed slides bear handwritten numbers that refer back to this notebook, providing information about when, where and in which context the photos were taken (figs 1&2). The materials used were detailed one after the other in the lists of film rolls, and hence redundant numbers for the 35mm and medium format film produced by Kodak, Agfa and Perutz exist. Anyone seeking to identify the film numbers from this expedition has to take the type of photographic film used into account (see figs 3&4).

However, the written documentation pertaining to the film material is incomplete, meaning that in some cases it is impossible to match the descriptions to the photographs. The information on the photographic images is supplemented by details of exposure times, film speeds and light conditions. At the end of the notebook we also find a shipping list.

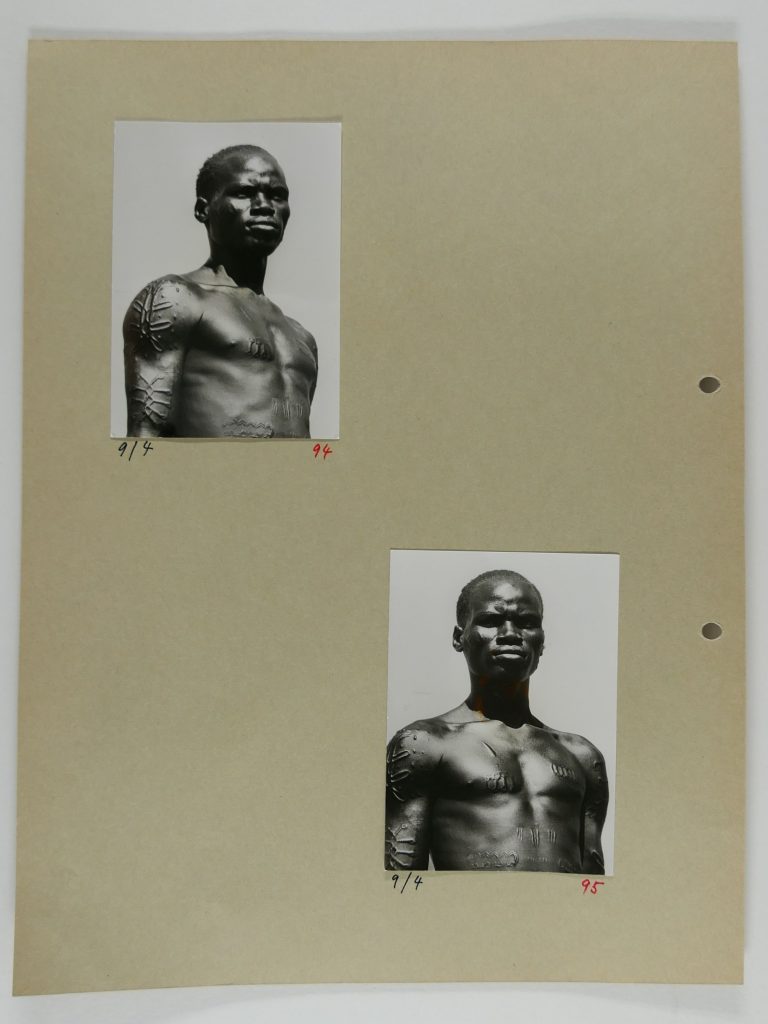

Prints and negatives in context

Some of the slides and negatives in the archives include references to document folders where samples of photographs on various topics had been pasted.[3] The numbering on round white labels (figs 5&6) corresponds to the consecutive numbers in the folders found in sets 1044 and 1045 (fig. 7). In the folders for the set numbers 1040 to 1043, some of the prints have been matched with their corresponding negatives (fig. 8). Here the labelling follows the following pattern: sheet number (= sleeve) – row number (in the sleeve) – negative number (fig. 9).

Lists of images and topics

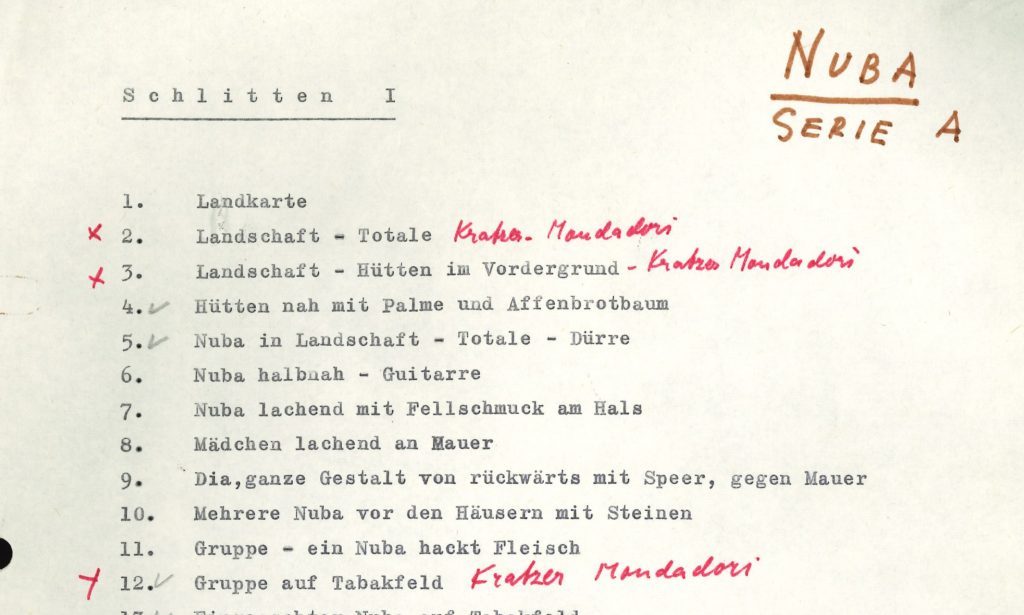

The lists that Riefenstahl created for assorted purposes correspond to the various Nuba groups and other ethnicities.[4] In some of the lists we can discern notes about subjects that had been published (fig. 10), but none of the objects in the archive have hitherto been matched to these notes with any degree of certainty. Riefenstahl categorised individual sets as relating to a particular theme and relabelled them accordingly (fig. 11).

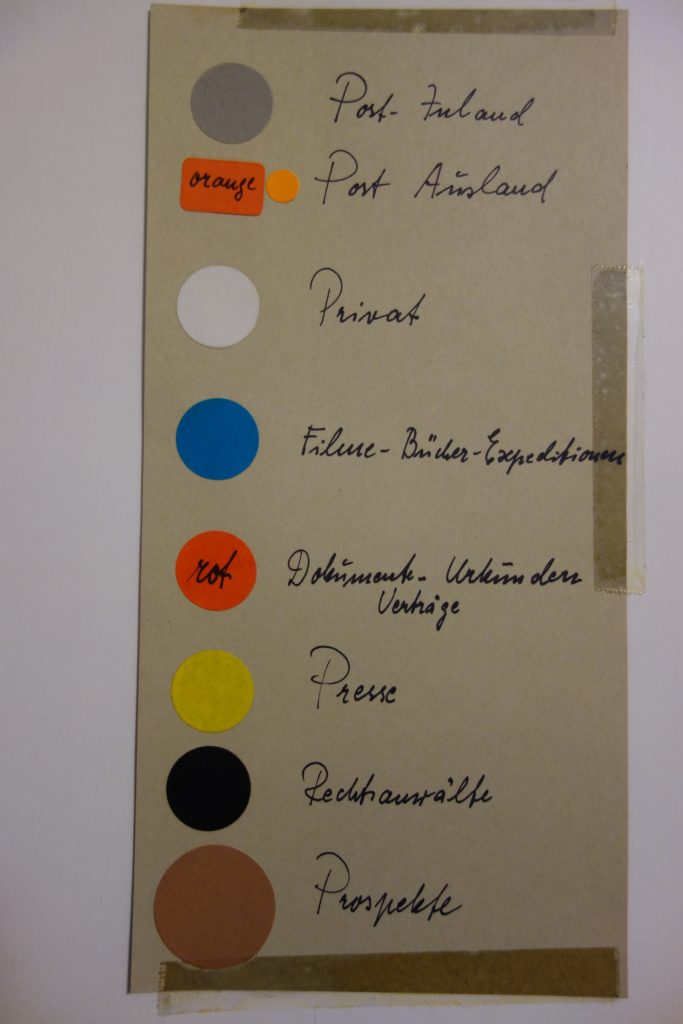

A legend with coloured labels

A key made up of round coloured labels provides an overview of various categories (fig. 12). These labels are found in many places throughout the photo archive, such as on the boxes containing sets of objects, on slide frames and on repackaging. Often several such labels are found on a single object. The descriptions of the categories are broadly defined and phrased in general terms. Without additional evidence detailing this process, it is impossible to determine whether it represents a systematic approach to labelling. The significance of the numbering found on some of the labels has yet to be determined (fig. 13).

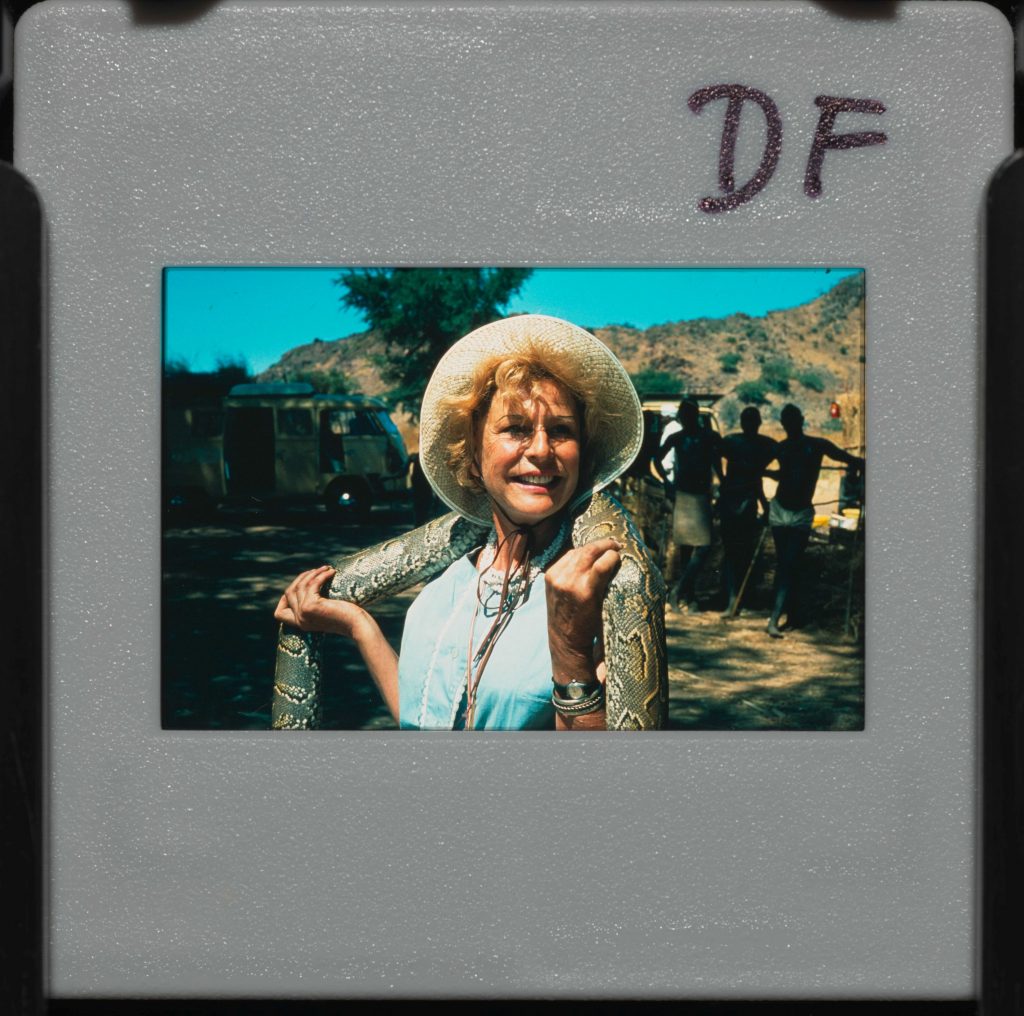

A number of other markings discovered during the registration of over 11,000 individual objects have yet to be deciphered. These include abbreviations (fig. 14), for example, which could conceivably refer to duplicates provided to publishers or magazines, but they might equally be the initials of people’s names (DH, DF, DM). However, no evidence exists to support either of these interpretations. In addition, the slide frames are inscribed with various symbols (fig. 15), but once again we have been unable to discover their meaning.

JH

Digitisation and AI-assisted image searches

The overwhelming majority of Riefenstahl’s photographs from the Nuba Mountains and surrounding regions was taken with 35mm cameras on colour transparency film. She was mainly interested in expressive, powerful motifs, but no thematic or formal classification of the photographs exists. Information as basic as where and when the images were taken, whether films are linked to any other contents, and the identities of the people shown is largely missing or present only in incomplete lists. The relationships between originals and duplicates or reproductions were generally not recorded and can be determined only by visually comparing the material.

As a result, thematic relationships and the circumstances under which the images were taken must be reconstructed through research. In many cases, the materials can only be interpreted by viewing and comparing the images – including those in other archives and in the publications. To accelerate the cataloguing process and provide greater ease of handling, all the 35mm material was initially digitised.

The digitised slides form the basis for the collaborative research with representatives of the Nuba communities. This was the only way images of all the motifs could be brought to Uganda for the workshops in order to be viewed and discussed there. The collaborative viewing of the photographs has two main goals: first, a graded classification of access rights for the relatives of people shown in the pictures as well as for researchers and the public and, second, the identification of the scenes and, wherever possible, the individuals in the photographs.

During digitisation, the contents of the various groups of objects belonging to the estate were kept together in order to preserve the original organisation of Riefenstahl’s working archive for future research. Riefenstahl grouped selected images according to categories which she subjectively regarded as important and which recur as chapter titles in her publications, such as “Requiem” as the heading for Masakin funeral ceremonies and “Die Kunst der Maske” (The art of the mask) as the title of the chapter on face painting among the warriors of Kau Nyaro. Descriptions such as “Nuba in Kleidern” (Nuba in clothing) and “Landschaft mit Hütten” (Landscape with huts) are an expression of Riefenstahl’s external perspective. The remainder of the slides are organised into a qualitative hierarchy, for example “Reserve”, “Zweite Wahl” (Second-rate quality), “Archiv“ (Archive) etc. – but often lack any further indication of their content.

Our second step was to digitise the paper prints which Riefenstahl made for presentations. The cataloguing process also involves re-sorting the images digitally in order to trace the evolution of Riefenstahl’s own system of categorisation. For this purpose, descriptors such as “Agriculture”, “Musical instruments” and “Ceremonies” were formulated in cooperation with Nuba representatives. These descriptors reference standardised vocabularies and constitute the first step towards providing fuller descriptions, since local perspectives cannot be precisely captured in this way. They serve both to restructure the holdings and to make them easily searchable. The terms can be freely combined to describe the images in greater detail and assign them to multiple categories.

In order to process the images on the basis of what they show, we were able to use AI image recognition software that employs an image search process being developed at Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin for the project “Human.Machine.Culture – Artificial Intelligence for the Digital Cultural Heritage” (funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media as part of the German government’s national AI strategy). This tool is especially helpful for reconstructing interrelationships between images and searching for different pictures showing the same individual. For example, there are several films of a traditional race for young women for which Riefenstahl provided no labels at all; she did, however, use individual images of the event in other contexts. After a delegate from Kau Nyaro had thematically categorised and annotated this series of images, the photos that had once belonged together were reunited by means of an image similarity search.

In the course of the collaborative research, many people were identified in the Kau Nyaro region who were still living. Thanks to AI, other photographs of the same people can be identified and labelled with the relevant information. Re-sorting the digitised images and adding metadata serves to prepare the image data so that it can be transferred to the Pan-Nuba Council for its own research.

KP

Conserving and restoring the photographs

The stock of Nuba photographs comprises a large number of prints, negatives and slides in a large variety of techniques and materials. The condition of the individual objects reveals evidence of active use. Most of the photographs bear multiple annotations on the reverse, and labels have been affixed or paper notes pasted on. This usage has led to significant physical damage, including scratches, creases and fingerprints as well as occasional tears and visible discolouration resulting from glue or adhesive tape applied to the backs of the photos.

A representative selection of large-format cibachrome photographs was pasted on black cardboard for display purposes. The photographs, negatives and slides were stored in cartons and portfolios which are unsuitable for conserving photographic materials. At the start of conservation and restoration work, and before the materials were digitised, all of the photographs were cleaned. Any overlying dust or grime was removed as were traces of glue and adhesive tape. Tears and sharp creases were reinforced and backed with Japanese tissue paper to prevent further damage during handling.

After each photograph was scanned it was placed in a new sleeve of archival photo paper. All of the cartons and portfolios were replaced with suitable boxes made of archival cardboard. Before the cibachrome prints were packed they were removed from their black cardboard backing because the material was damaging the photos.

Most of the negatives were stored in plastic sleeves or in glassine envelopes from the film lab, and these had been placed in commercially available document folders. The negatives were packed in sleeves of photo archive paper and closed filing boxes for conservation purposes. The framed color transparencies, most of which had previously been stored in a number of different plastic boxes, were also repacked in new slide boxes made of archival cardboard. The new packaging materials and storage facilities featuring controlled temperature and humidity ensure the optimal conditions for archiving these photographic materials in the long term.

HP/SP