Berlin State Library

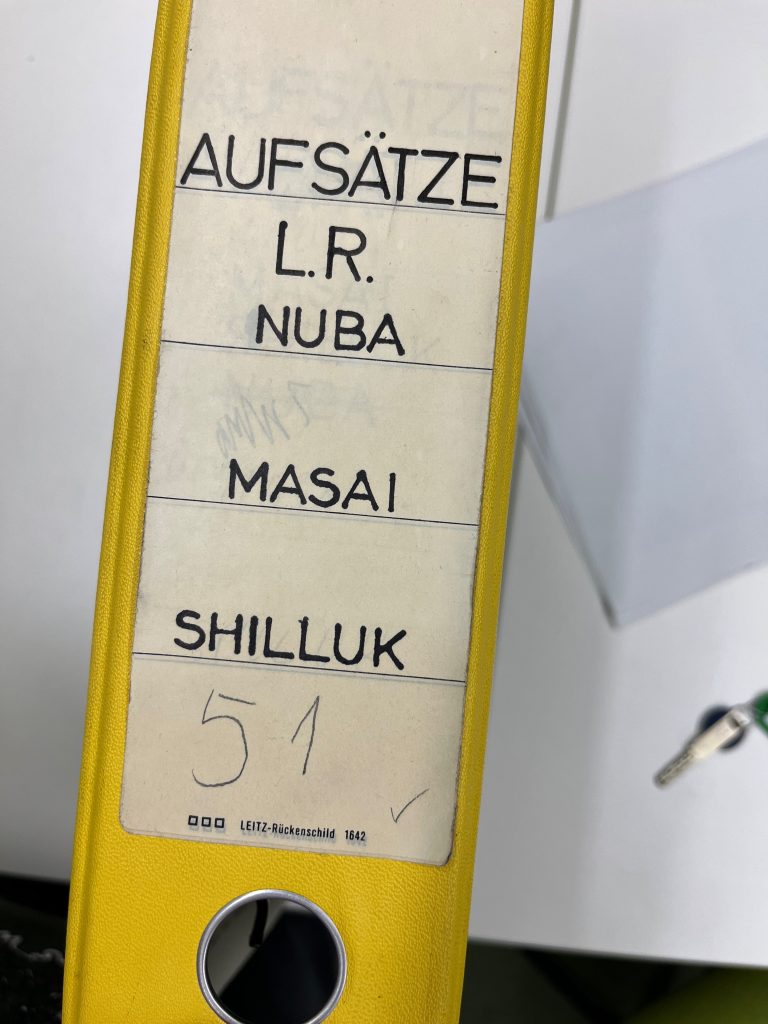

Legend to the archive holdings (photo: Hanns-Peter Frentz)

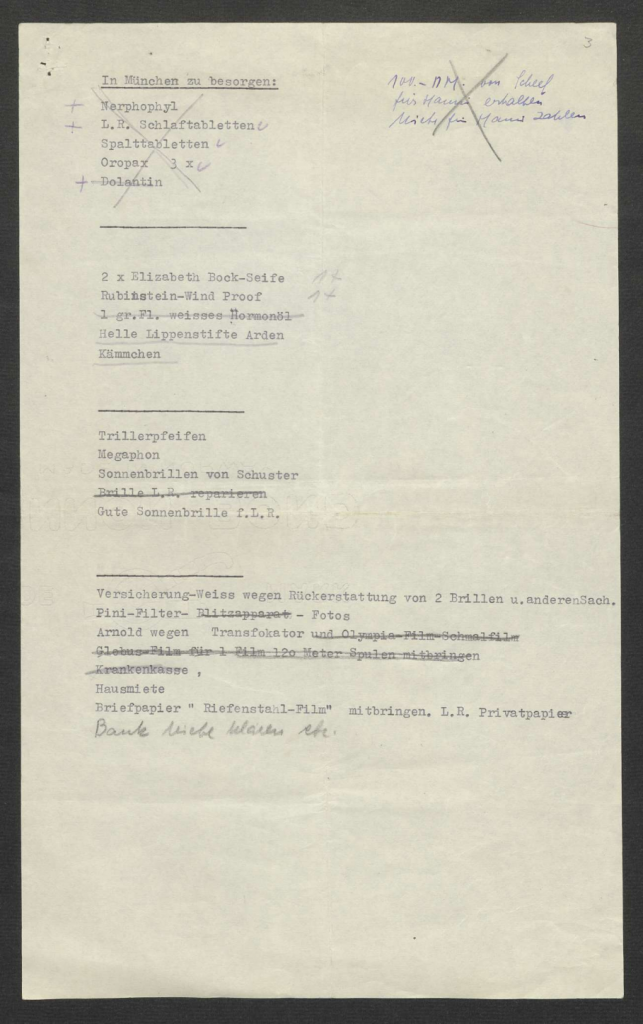

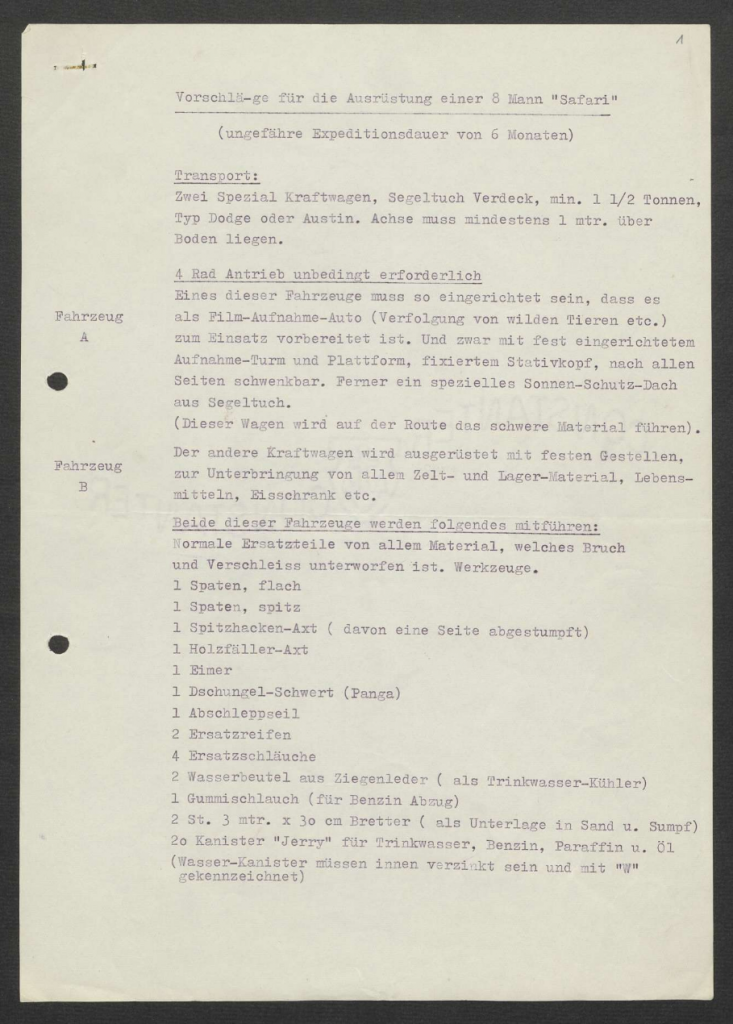

Legend to the archive holdings (photo: Hanns-Peter Frentz)

The written documents in the Riefenstahl estate

The written materials in Leni Riefenstahl’s estate, which are held at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library), comprise her personal and professional archive. The materials from the 1920s and the Nazi era are incomplete as some were lost or discarded at the end of the Second World War. There are, however, copious documents from the period after 1945. Riefenstahl and her staff worked tirelessly in the archive, constantly rearranging and reproducing the written materials, although it is quite possible that certain records were weeded out in the process.

This body of written documents is exceedingly important for researchers studying Riefenstahl’s work and personal history. It is a vital source of information on numerous key topics, such as her relations with the Nazi state and the regime’s major players (connections which continued after 1945 with those who survived the war), her life and work in the post-war period and her contacts with figures who played a role in the politics and society of the day, as well as with her staff and colleagues. One important aspect that stands out in a number of previously unknown documents is the reception of her work and how it was viewed in the realms of popular culture. The enormous wealth of material showcases many different sides of this controversial artist. Her cinematic projects before and after the war – including those films that were never made – and her work as a photographer and author are documented in screenplays, notes, research records, etc. It is often possible to reconstruct in detail the process of how her works came about.

Correspondence

Riefenstahl’s abundant correspondence reflects her extensive network of professional and private connections. She kept a separate collection of letters from prominent contemporaries. In addition to her private correspondence, this section primarily consists of written communications from her production companies, including documentation of all the different areas that Leni Riefenstahl Produktion was involved in (film and photo production, issues about rights and distribution, etc.). Finally, the extensive correspondence with her lawyers reveals the many legal disputes, both personal and work-related, that beset Riefenstahl. The exchanges of letters are indicative of her international reputation and reach, with her network of professional and private contacts extending far beyond her native Germany – not only to Japan and the United States but also to many European countries, including the UK, France and Italy.

Personal documents

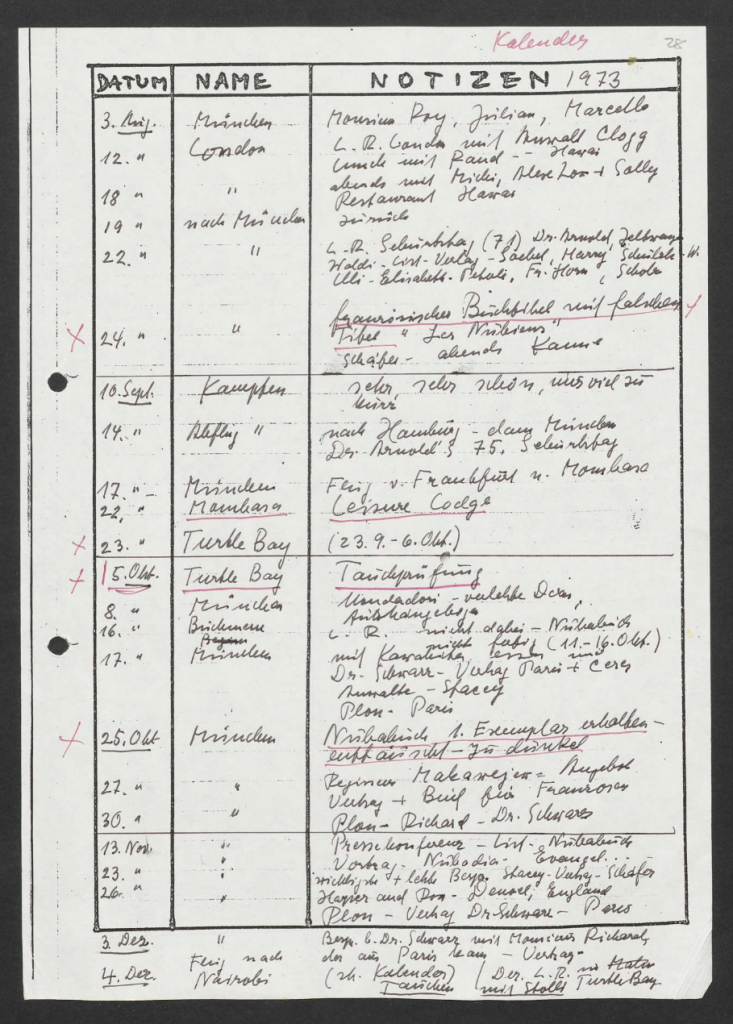

The personal documents section includes appointment diaries, address books, materials relating to her trips to Africa, certificates and other items that provide important, detailed information about Riefenstahl’s life and career.

Collections

Finally, the collections section contains an abundance of material relating to Riefenstahl’s work and personal life that she compiled on an ongoing basis through to the end of her life. These documents, which date back to the start of her career in the 1920s, include articles from the German and foreign press, reviews, publications and audiovisual media.

Library

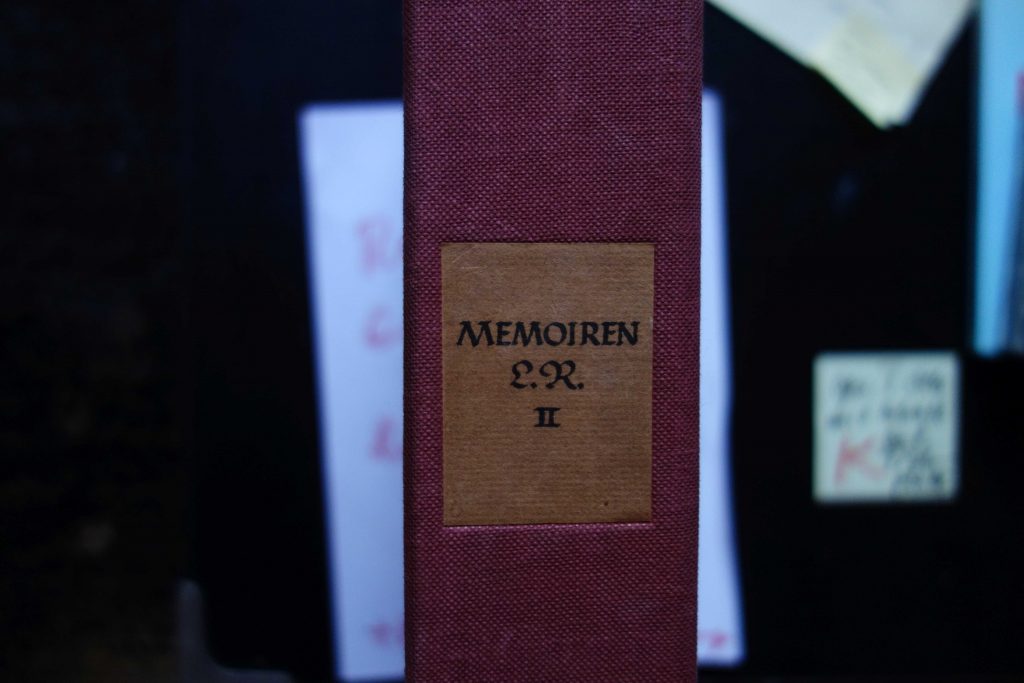

Finally, the collections section contains an abundance of material relating to Riefenstahl’s work and personal life that she compiled on an ongoing basis through to the end of her life. These documents, which date back to the start of her career in the 1920s, include articles from the German and foreign press, reviews, publications and audiovisual media.

Curated archive: The written legacy

Leni Riefenstahl’s written estate, archived in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library, or SBB) under the call no. “Nachl. 590”, comprises over 750 items housed in files, archival boxes and custom-built linen boxes, which Riefenstahl and her secretaries used for organising and storing the archival material. During our initial assessment, we sorted the material into the following categories with respect to the type of holdings and their call numbers:

– Works (call nos 1–128)

– Correspondence (call nos 129–491)

– Biographical documents (call nos 492–566)

– Collections (call nos 567–750)

Within these categories, the holdings were left in their original receptacles and inventorised together with brief lists of contents, including details of where they had previously been kept in Riefenstahl’s home. Alongside manuscripts, film scripts, notes (c. 800 individual documents), biographical documents (c. 700 documents) and the dossiers compiled by Riefenstahl and her staff (c. 210 items), the largest single category consists of professional and private correspondence (c. 17,000 documents). In this section of the holdings, the colour of whatever container they were being stored in sometimes indicates a monohierarchical archiving system, which inevitably led to multiple copies being preserved. Colour coding served as an aid for organisation – at least intermittently and presumably echoing Riefenstahl’s creative processes in the field of filmmaking (fig. 1):

– white for private correspondence

– grey for domestic post

– orange for international post

– red for documents, certificates and contracts

– blue for films, books and expeditions

– yellow for press cuttings

– black for legal correspondence

– brown for brochures

– green for financial matters

For example, white was used for the correspondence with the production designer Isabella Ploberger-Schlichting on how to credit her for the film Tiefland as well as for letters from Arnold Fanck containing ideas about screening films in Africa. Blue was used for reports, letters and newspaper cuttings relating to unrealised film projects such as Der Nil. Riefenstahl’s published essays were colour-coded yellow, including texts about the Nuba (fig. 2). Black was assigned to legal correspondence such as that concerning the planned film version of Riefenstahl’s Memoirs, which were published in 1987.

Material about Africa

The written material about Africa, which has been integrated into Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin’s cataloguing and digitisation project (funded by the German Research Foundation, or DFG), comprises around 220 items containing thousands of individual documents. They include project summaries, notes, diaries, letters and assorted archival documentation such as diplomas, filming permits, receipts, lists of materials, travel documents and individual photographs.

All these documents from the past offer insights into Riefenstahl’s travel plans – everything from her personal, professional and organisational preparations (fig. 3) to the expeditions themselves, before she ultimately presented her projects as effectively as possible to the general public through the medium of photographs, films, publications, lectures and exhibitions.

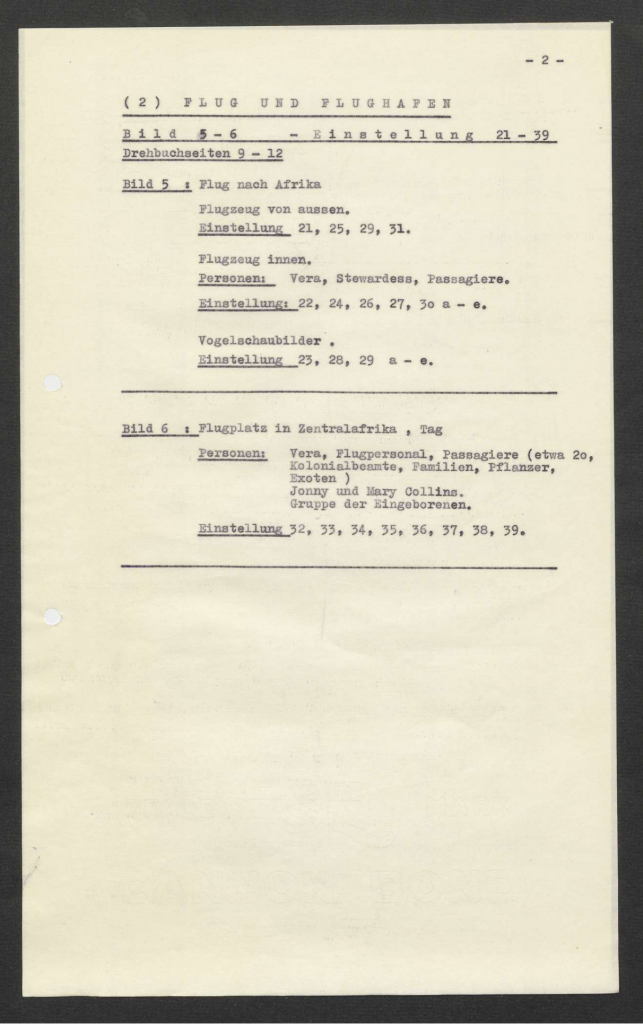

While the written legacy spans almost a century, from about 1920 to 2018, the bulk of it dates from the time after 1945. This was also the period when Riefenstahl supervised the process of archiving the results of her photographic and cinematic renaissance on the African continent. She began this professional sea change in 1956, with her first trip to Kenya and Uganda for a film project about the slave trade (figs 4&5), which she followed up by participating in an expedition undertaken by the Nansen Society (1962/63). Her engagement with Africa continued until 1982, when she presented her fourth illustrated volume, Mein Afrika (My Africa) to mark her 80th birthday. Moreover, Riefenstahl compiled notes for her memoirs, which include overviews of her experiences in Africa (fig. 6).

Curated data: Cataloguing and digitisation

Our goal is to catalogue Riefenstahl’s estate in detail so that Nuba representatives, the research community, journalists and interested members of the public from all over the world are given the opportunity to engage with issues both fundamental and complex. These include the individuals who participated in Riefenstahl’s trips in various eras; the process of setting up assorted companies such as Stern-Film GmbH; and documentation about sponsors or the equipment used on the African expeditions (fig. 7). Questions about conserving the holdings are not the only reason why merely making the original materials available would be insufficient.

Working collaboratively to provide digital access to the sources in the estate will ensure that textual, visual and audio materials receive equal attention. At SBB, this is based on a sustainable IT infrastructure, uniform standards for metadata and authority files, high-resolution digital files and compliance with legal and ethical requirements. Reliable technologies offer optimum support for providing, accessing and reusing research data.

The cataloguing data for the written materials in the Riefenstahl estate will be stored in the Kalliope-Verbundkatalog. Over 1,300 citable documents are already available to scholars via a unique identifier. In addition to providing descriptive data about contents, size, participating actors, chronological information and local references to the archive materials, selected objects will be digitised. Subject to copyright considerations and usage rights, these digital copies will be made permanently accessible free of charge via the Digitalisierte Sammlungen platform. The digital objects will contain metadata and can be viewed and used via the DFG Viewer, an IIIF and OAI-PMH interface, or as PDF downloads. Each format will have a unique identifier.

People using the central Stabikat reference system to research, for example, “Riefenstahl Film GmbH” will find numerous references to printed and digital objects, including the digitised archives from Leni Riefenstahl’s estate. The Integrated Authority File (GND) plays a central role in the cataloguing project, creating reliable navigation points that allow people, companies and thematic references to be individually recorded and related to Riefenstahl’s life. The focus is not limited to the objects in the legacy, but also covers their digital network-like interrelationships via people, entities, places, themes and works. The shared use of thesauri and standard vocabularies like the GND allows Riefenstahl’s estate to be virtually collated in order to develop services that can facilitate research and presentation in the future.

KT