Deutsche Kinemathek

Shamsoun Khamis in the storage of the Deutsche Kinemathek (photo: Ala Kheir)

Shamsoun Khamis in the storage of the Deutsche Kinemathek (photo: Ala Kheir)

The film recordings at Deutsche Kinemathek

Rather than forming a single complete work, the film footage of the Nuba Mountains was made on four trips to Masakin and Kau in 1964/65, 1968/69, 1974/75 and 1977. The holdings comprise a total of around 535 items, primarily film cans containing 16mm original reversal films and rushes, as well as magnetic tapes in various formats, audio cassettes, assorted video formats, 8mm rolls and 16mm black-and-white original negatives and copies. There are around 380 cans of visual material, of which some 204 are just small cans mostly containing single film strips or even individual images, while around 137 are cans and cassettes with sound only. The total length of the visual stock (without video material) is estimated to be around 35,000 metres or 54 hours, and the audio material is thought to comprise 47 hours.

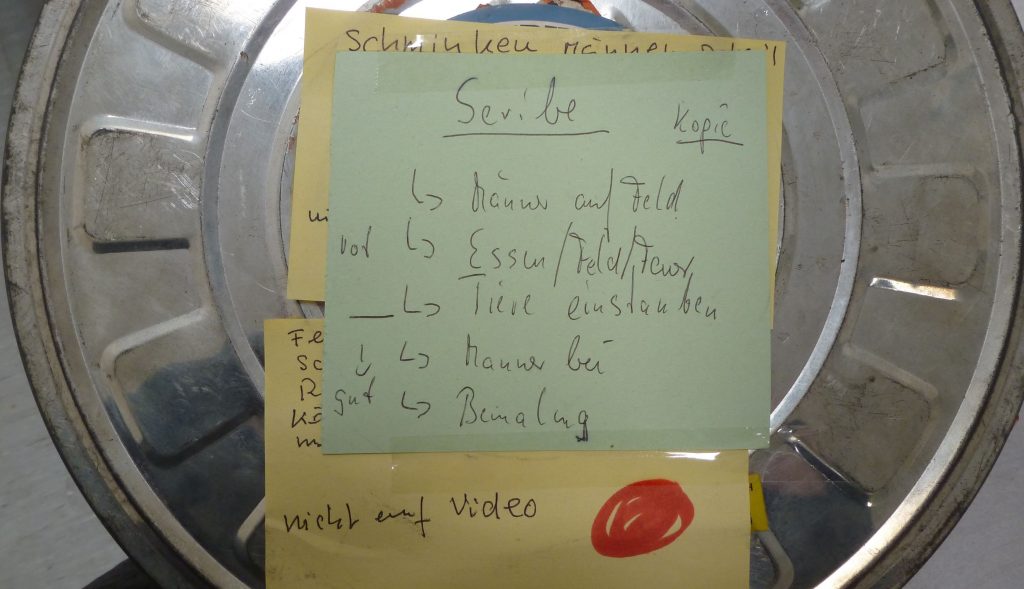

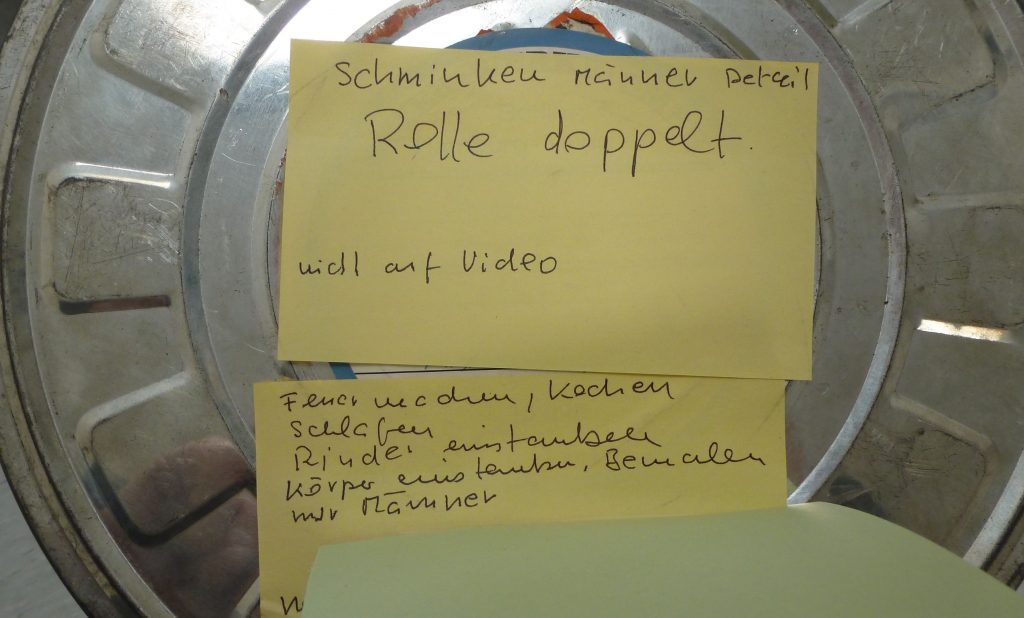

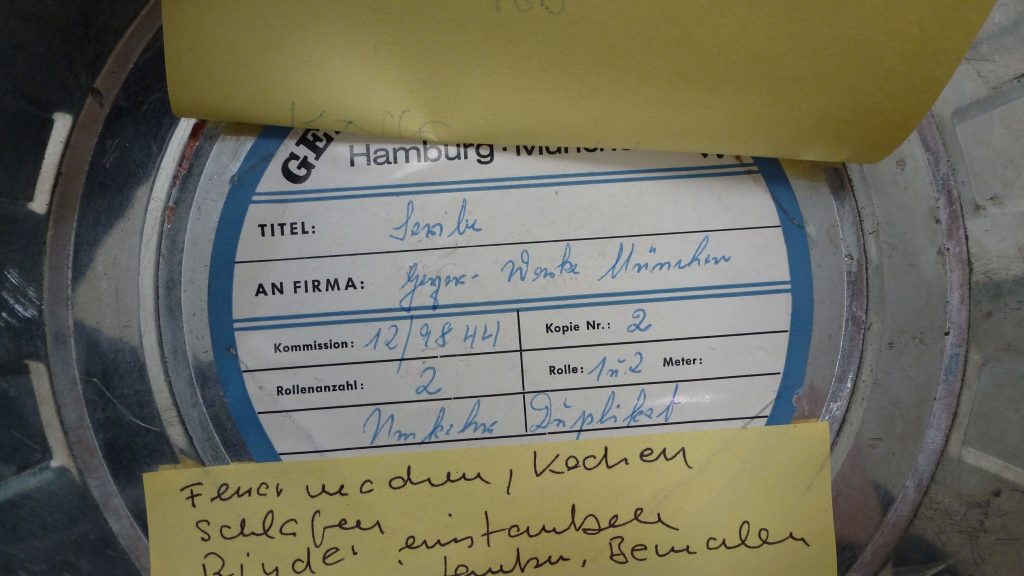

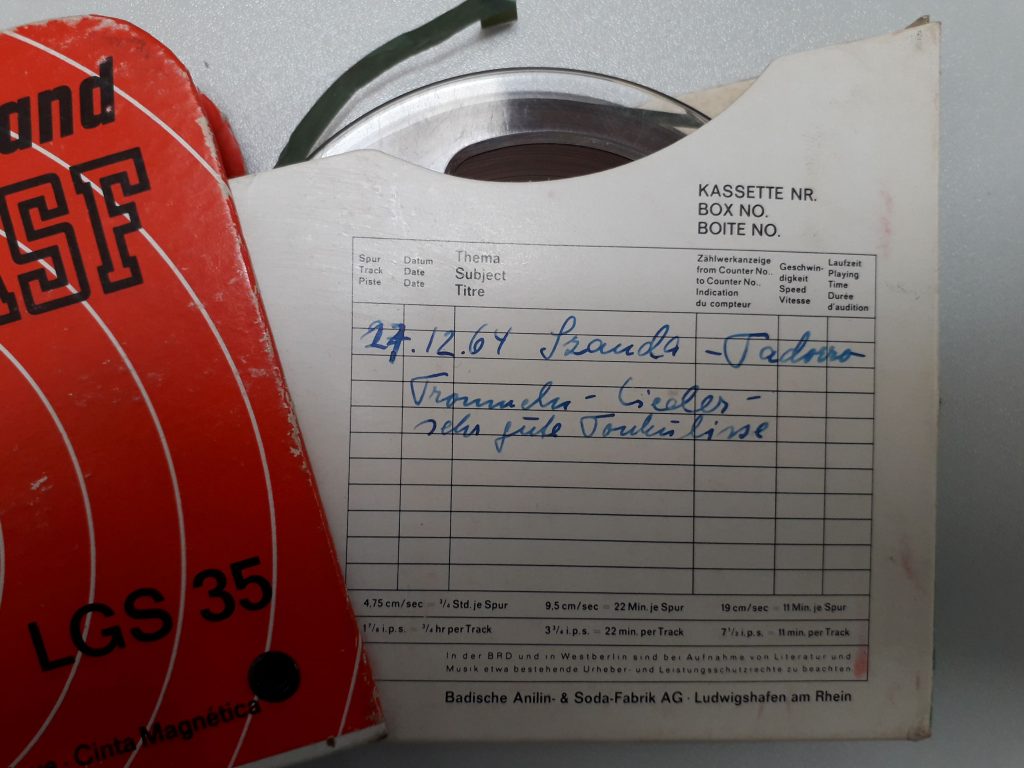

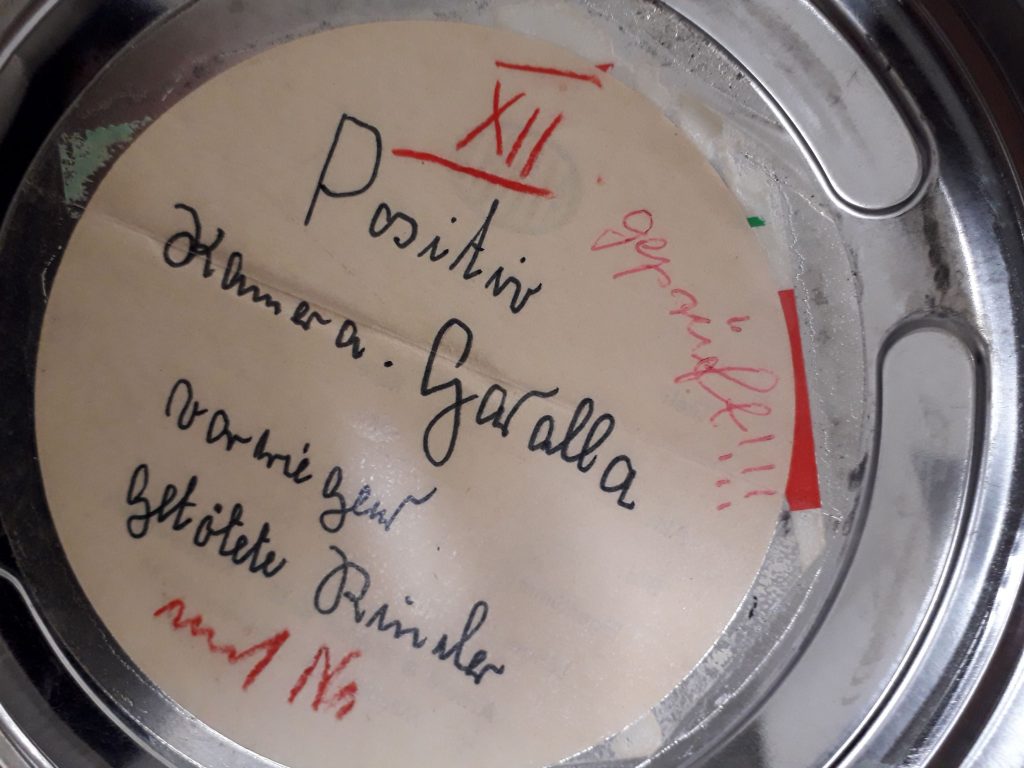

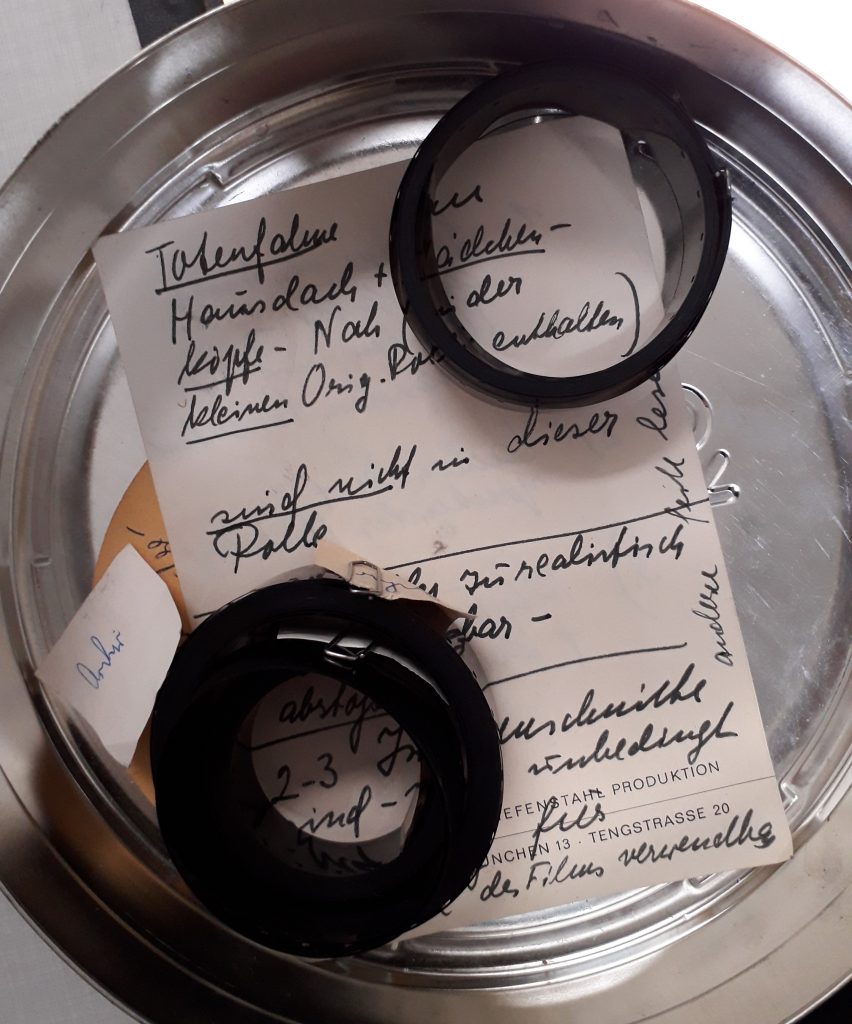

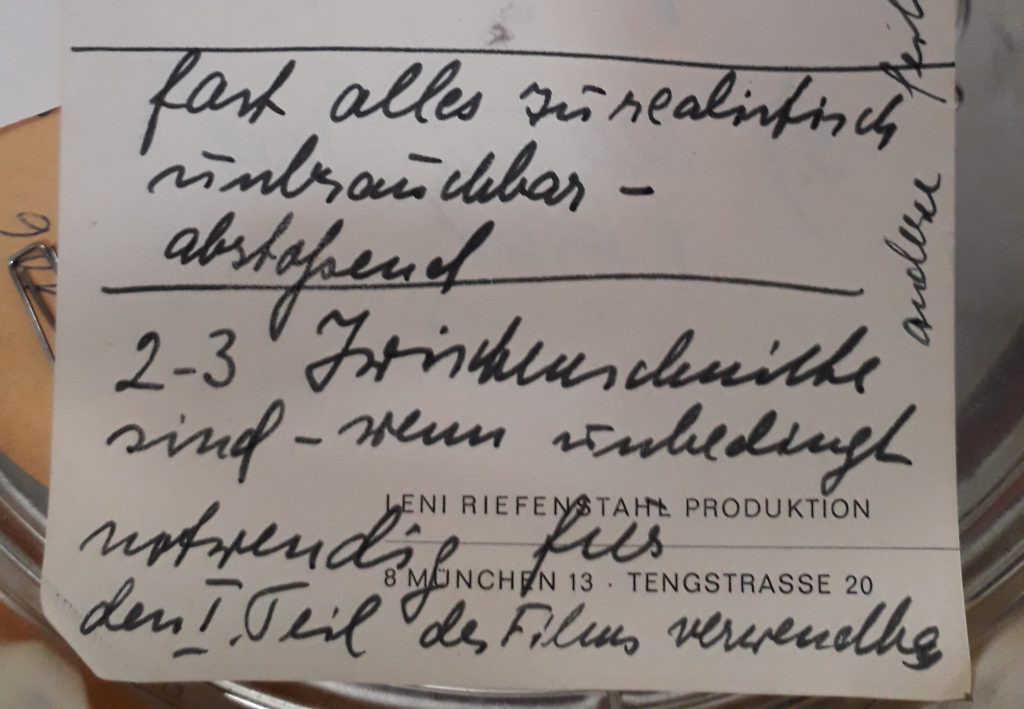

There is currently believed to be no inventory detailing this stock. So what can be done to verify that the holdings are complete, organise the materials according to the year when they were created, differentiate originals from rushes and match the audio with the images? The labels on cans and cassettes are of limited use because various different systems have been used for labelling and categorising the objects. Some of the cans have multiple overlapping stickers and post-it notes affixed to them, the handwriting revealing them to be from the film lab, from Riefenstahl herself or from one of her staff (figs 1–3).

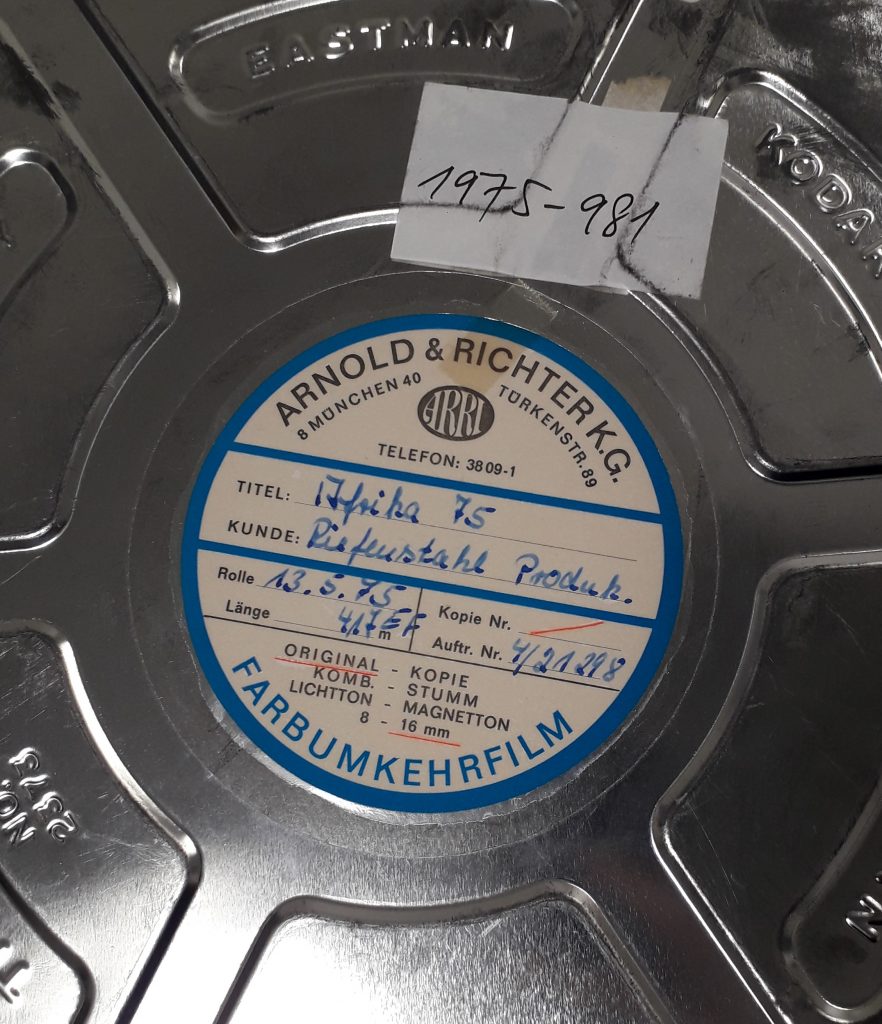

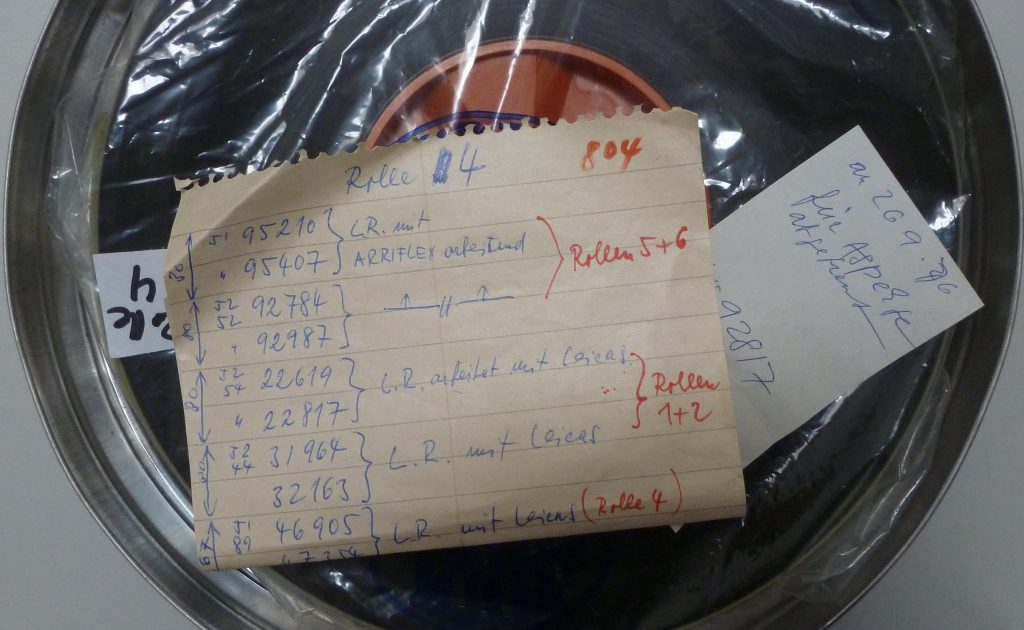

One numbering system – with the year of travel and a sequential number – exists for original reversal films from 1968/69 onwards. It has, however, not been consistently applied, which means no conclusions can be drawn from it about the original size of the holdings (fig. 4). On the first journey in 1964/65, it seems that nobody saw the need even to number the cans, let alone label them with the year. In contrast, some of the audio material was marked with the exact date, along with details of the contents. On later trips, however, many cans were labelled only with the year and place. Synchronised sound is rare, and it seems that in most cases some original audio was recorded during filming, as well as independently of it (fig. 5). A glance inside the film cans makes it clear that knowing their number gives little indication of the volume of the material. The size of the rolls contained therein varies between 20 and 480 metres, and while some cans hold several rolls, a few are just individual strips of film that have been combined using paperclips to create small rolls (fig. 6).

The proportion of originals to rushes varies greatly from trip to trip. Whereas there were around 8,000 metres of original reversal film in 1964/65 to around 6,000 metres of rushes, a similar amount of original reversal film in 1974/75 contrasts with just under 2,000 metres of rushes. It seems that Riefenstahl worked above all with the 1964/65 recordings. Evidence for this is provided by the 204 small cans which apparently contain leftover material from the rushes that had been sorted out and retained for a potential future use. Unlike the originals and the rushes, these canisters are thematically labelled with titles such as “Seribe”, “Landschaft” (Landscape), “Totenfest” (Festival of the dead) and “Ringkampf” (Wrestling), which correspond to the chapter headings of Riefenstahl’s books of photographs. The holdings which have apparently been touched the least are the 2,500 metres from 1977, for which there seem to be virtually no rushes (fig. 7).

AW

Working with the film footage

Identification

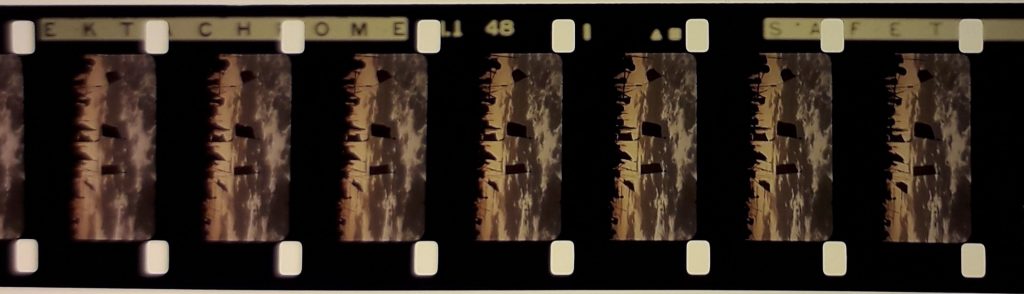

The first goal of the identification process was to distinguish between originals and copies. In the case of films with no date marked on the can, it was also necessary to determine which trip they belonged to. These tasks were made more difficult by the divergent and overlapping systems used for labelling and organisation. We were able to identify images from the 1964/65 Sudan expedition thanks to the edge codes on the unexposed stock of Kodak’s Ektachrome colour reversal film, which is marked with symbols denoting the year of manufacture (fig. 1). Studying the edge codes was crucial for verifying the provenance of the originals. The varying lengths of the film rolls suggested that the camera rolls had been edited, and this was confirmed by the foot numbers. Like edge codes, foot numbers are exposed onto the film by the manufacturer and represent sequential numbers that are unique to every roll of film. Splices were additional indications of editing. Several series of foot numbers within the same roll show that multiple camera rolls had been joined together to form a larger roll, with splices at the places where two rolls had been joined. In contrast, missing numbers show that sections had been cut out (fig. 2).

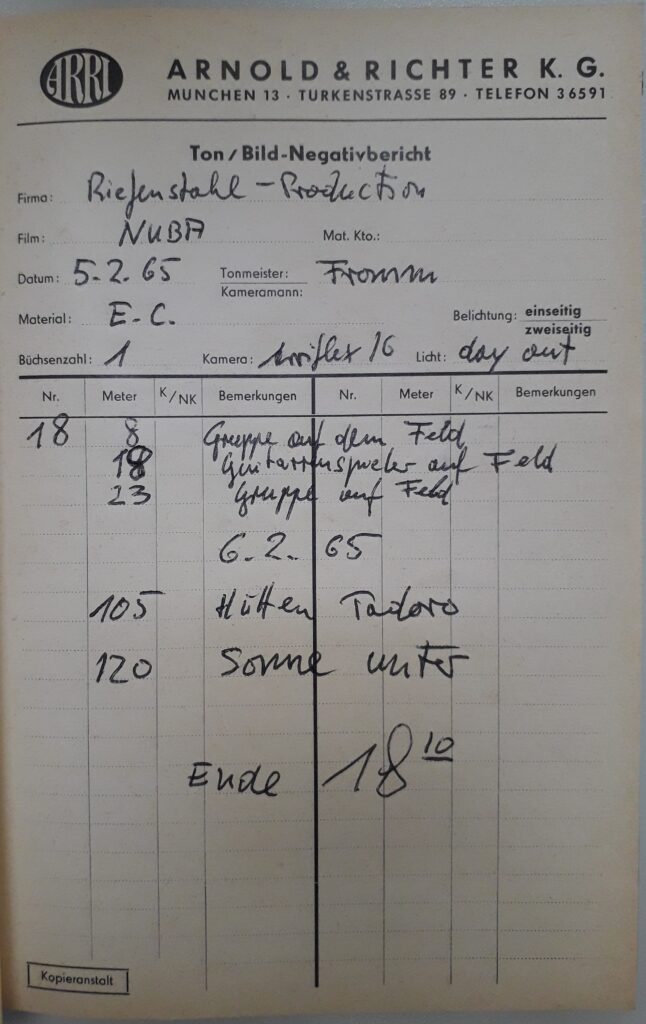

The vague nature of the labels on the cans means that the exact dates and places of when and where the footage was shot are generally unclear. The audio tracks, which were produced at the same time and sometimes include such details, may help to clarify this issue. To this end, the sound recordings and film footage need to be examined in detail. Another crucial source are the film negative reports produced by the camera crew, documenting what was shot on a given camera roll; these are partially extant for 1964/65. Random sampling has shown that the roll numbers in the negative reports correspond to the numbers on filmed slates in the original reversal films (figs 3&4).

The cameramen

A significant amount of material from the film footage which Riefenstahl provided for television reports and documentary films shows her shooting with the Arriflex camera during a wrestling match. This creates the impression that she personally operated the camera during filming. The can with the original reversal film of this footage contains a list of selected shots, probably in Riefenstahl’s handwriting, that show her with the Arriflex film camera and with Leica still cameras. Also found in the can was a note that these shots were cut out in September 1976 for the TV magazine programme Aspekte (fig. 5).

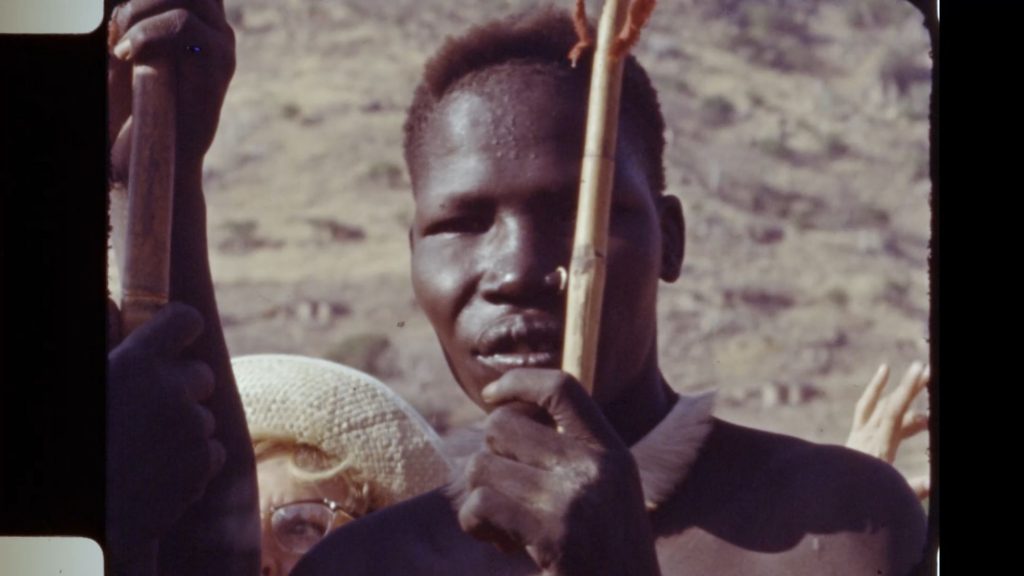

In fact, however, this footage served as advertising for one of her most important sponsors – it was actually Gerhard Fromm who was responsible for the camera in 1964/65 and Horst Kettner from 1968 onwards, while Walter Hailer was involved as second cameraman, at least in 1964/65. Riefenstahl does not mention these three names either on the labelling on the can or in the working notes contained in the cans themselves. However, these materials do identify the Sudanese cameraman who remains nameless in Riefenstahl’s reports: Gadalla Gubara was responsible for shooting the earliest footage of the 1964/65 expedition, and was then succeeded by Gerhard Fromm.

It is unclear why Gadalla Gubara left the project. Notes by Riefenstahl found in cans containing sundry material state that his footage of slaughtered cattle was “too realistic” and therefore “unusable” (figs 6–8). Similarly, Gadalla Gubara’s images of a man dancing with a belt covered in little bells are kept in a box labelled as sundry material. This raises the question of the extent to which the Sudanese filmmaker had his own approach to documenting the lives of his compatriots and whether this approach may have been incompatible with Riefenstahl’s wishes. His experiences during the filming are a matter for further research.

Riefenstahl on camera

Riefenstahl was often filmed with the Sudanese protagonists of the documentaries, especially during the 1974/75 expedition. This footage is not limited to shots which clearly served as advertising for her numerous sponsors, for instance showing Riefenstahl filming with the Arriflex during a wrestling match or while distributing medicines. Riefenstahl’s presence is also evident in a very different way in incidental shots at the beginning of scenes, when the camera was already rolling but she was still in the shot, giving last-minute instructions to the protagonists or the camera (figs 9&10). These proofs of her presence are confined to a small number of single frames that are easy to miss and can be most effectively identified using frame-by-frame playback after the material has been digitised. These images allow us to study Riefenstahl’s interventions in the events being filmed.

Purpose of restoration

The digitisation and restoration process is aimed at the original reversal films. The ratio of originals to copies shows that the originals provide the most complete record of the footage shot in the Nuba Mountains. Edge codes and splices provide evidence of editing and omissions in the originals, allowing us to reconstruct the camera rolls. It is vital that we work out how the camera rolls, photographs and written records are related in order to gain a deeper overall understanding of the large volume of material and more specifically to facilitate the research.

AW